All The Weird Chords

Can you play a C-7b9#11? How about a A7sus2#5? Or a C7/E? Though these chords may seem confusing, learning just a little bit about how this notation works can unlock every single chord name, no matter how long or complicated.

Introduction to musical chords

To better understand these chord extensions - a term that means the notes on top of basic chords, read up on our blogs about triads, seventh chords, intervals, and less essential but still interesting: augmented and diminished chords. However, a good review is below.

The basic building blocks of chords are called triads - a set of three notes a third apart from each other. They are how chords are named, meaning that any chord that starts with the letter C is built on the C triad which has C as the first note, any chord that starts with the letter D is built on the D triad which has D as the first note, etc. Here are a few examples of major and minor triads. (Hint: here’s a refresher on how to read sheet music)

That just leaves how to read all the text after, such as sus2, or #9, etc. You’re in luck, that’s what this blog is about! There are quite a few of these, so this Boston Piano Lessons blog will both teach you how to understand what all of this means, and hopefully serve as reference to specific chords in songs you are trying to learn.

Overview: Types of Musical Chords & how to read them

The most important thing to start with is to see which letters are uppercase and which letters are lowercase. You will only find one or sometimes two uppercase letters, with the second uppercase letter coming after a slash (or far more rarely, a vertical line).

The first uppercase letter is the most important one, as it designates which triad the rest of the chord (the extensions) are built on top of. The lowercase letters (maj, sus, etc.) are modifications or specifiers that denote something about the chord. Let’s go through all of them now.

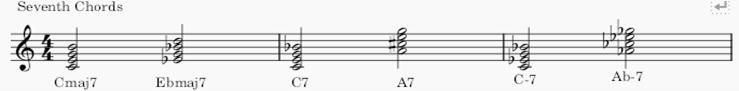

Seventh Chords

You can check out a much more in-depth dive into seventh chords here, but a short summary is below.

It is important to understand these, as most chords in jazz, and almost all of the chords that you’ll find with the extensions, are seventh chords. These chords are a triad with another note on top a third away from the top note, making it a seventh away from the bottom note - by default, with the extensions on top of those.

In jazz, it’s almost like the seventh chord is the basic building block rather than simpler triads. The lowercase letters “maj” means major, and it is a type of seventh chord. There are three kinds of common seventh chords: major (denoted by maj, or in some older texts a triangle symbol), minor (denoted by a –, m, or more rarely, min) and dominant (denoted by no symbol or text before the number 7 in the chord name, so A7, Ab7, D7, etc.). Here are some examples of these three types of seventh chords:

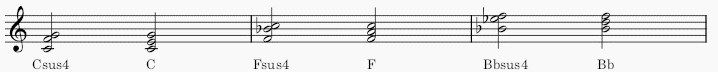

Sus Chords

Sus chords are a special type of chord, as they modify the foundational triad of the chord, and then can have extensions on top. They do this by changing the third of the triad. The third is the middle note of a triad, as it is a third away from the root - the root being the first note of the triad and the note that the chord is named after. The fifth is the last note of the triad, as it is a fifth away from the root.

There are two kinds of sus chords, or suspension chords. They are so named because in classical music, these chords were used in a very specific way - a note from a previous chord was kept in the new chord (or suspended), and then resolved down to the normal triad. It is exclusively used as a bridge between two chords. Here is an example of a very common use of a suspended chord in classical music:

In Jazz and modern music, the suspended chords are no longer used in this way, and are individual chords in themselves and used so.

A sus2 changes the third to a second - so in a C chord, which usually consists of C E G, a Csus2 would contain a C D G. Here are some examples of sus2 chords and the triads they modify.

A sus4 changes the third to a fourth - so in a C chord, which usually consists of C E G, a Csus4 would contain C F G. Here are some examples of sus4 chords and the triads they modify:

Sus chords have a very washed out sound, likened to the pastel colors of the music world, if regular triads were bold colors. They are used to this effect in songs like Free Fallin’, by Tom Petty, which alternates between a D and a Dsus4 in the identifying guitar part:

And in songs like Pinball Wizard, by the Who, which uses a series of alternating sus4 chords and their corresponding major chords as their main melody line:

Slash Chords

When chords have two uppercase letters, they are almost always separated by a slash. This means that you play the chord on the left side of the slash, with the bass playing the note on the right side of the slash. You can think about it kind of like fractions, with the numerator (the left side of the slash) being on top, and the denominator (the right side of the slash) being on the bottom.

On piano, this is effectively separating the right and left hand, with the right hand playing the chord, and the left hand playing the specified bass note. Here are some examples of slash chords:

Slash chords are used when the bass has a very distinctive line that is important for the song. For example, in the song Feelin’ Good, with this cover played by Muse, the bassline is four descending notes, which feels like the backbone of the song.

Another song that uses slash chords is Landslide, by Fleetwood Mac, which uses a G/B (a G chord with a B in the bass) as a nice bridge between the C and the A minor, both on the way up and down, making a cohesive sequential bassline that sounds very pretty.

Polychords

Polychords are very, very rare, only really used in some niche jazz music, and are included here just for completion's sake. Polychords look like slash chords, but the divider between them is a vertical line, not a slash. They mean the left side chord is played on top, and the right side chord is played on bottom. In slash chords, the letter on the right denotes a note, and in polychords, the letter on the right denotes a chord. The easiest way to play them on piano is a triad in each hand. Here are some examples of polychords.

It is difficult to find songs with polychords, as often the chords in jazz have so many notes that they can be denoted in several ways, sometimes as a polychord, sometimes as a slash chord with extensions. Again, polychords are very rare, and often just a kind of notation, and are included in this blog just for completion’s sake.

Personally, I have only played one piece with a polychord, and it was specifically written to try and use polychords. A grasp of extension notation, explained in the next section, is more than enough to play through anything you want to play.

Chord extensions

Now that we’ve defined the text that comes after a chord name (such as sus, maj or /), it’s time to get into the numbers that come into naming a chord. Things like b9 (flat 9) or #11 (sharp 11) are extensions on top of normal seventh chords that are important in adding color to simpler chords, and give jazz its distinctive sound.

For more info, read up on our blog on intervals, but a quick review is below.

An interval is the distance between two notes and is calculated by the number of notes between them. For example, the distance between C and E is a third, because it’s three notes - C, D, and E. The distance between C and G is a fifth, because it’s five notes - C, D, E, F, and G.

However, the magic of extensions happens when you have more than an octave (or an eighth), which is the distance between a note and the next note of the same name, such as a 9th, 11th, 13th, etc. For example, a C7b9 is a C7 chord, consisting of C E G Bb, with a flat 9 on top, a Db, totaling to C E G Bb Db.

If you’ve been paying attention, you might ask - why is it that it’s not a flat 2? A D is just a second away from a C, so why not use that instead of going past the octave and making it a 9?

This is because when you are inside the octave (in chords discussed previously like a sus2, or in diminished chords, also known as b5) the numbers are modifications to the foundational triad, while in chords that have extensions (going past the octave to 9, 11, 13, etc) the chords are in their standard triad (or in jazz, the standard 7th) form and have these extensions added to them. It adds more notes to the chord rather than changing the notes of the chord. These added notes, or extensions, are the magic that makes jazz so beautiful.

To figure out what notes to add, you just count to the number denoted by the extensions from the root note. You can make this easier by subtracting 7, and counting inside the first octave. For example, a C #11 is 11-7=4, so a fourth from C is F, and making it a #11 makes it an F#.

It is important to note that all extensions are by default from the major scale, so any modifications (like # or b) are modifications to the default note from the major scale. Do not make the mistake when reading extensions to minor seventh chords that the extensions are minor as well - they are by default from the major scale! For example, in a C-13, the 13 in the C minor scale would be Ab, but in the C major scale would be A, and since extensions are major by default, a C-13 would contain the original C-7 (C Eb G Bb) plus the extension 13 (A).

Here are some examples of common extension chords:

The 6/9

The only time when a slash does not have a letter after it, but a number. In this case, the 7th is not included, and the chord has the regular triad with a 6 and a 9 extension added on - this is a common ending chord in jazz, as it has a beautiful ambiguity but also finality to it. Here are some examples of 6/9 chords.

A song that uses the 6/9 as its ending chord is Ruby My Dear, by Thelonius Monk

The 7b9

The flat 9 is commonly used to add even more dissonance to the already dissonant 7 chord, making the resolution to the next chord that much more satisfying. Here are some examples of flat 9 chords.

A song that uses a b9 to dress up a dominant 7 is Autumn Leaves, this performance by Bill Evans Trio, which uses a B7b9 before satisfyingly resolving to the Em chord.

The maj7#11

A beautifully dissonant chord, without a specific function - more a great addition. Here are some examples of #11 chords.

A song that uses a #11 is Bob Dylan’s Feel My Love, performed by Adele, which uses a C#11 as a gorgeous start to the chorus.

Conclusion: understand Musical chords by playing them!

This blog completes our series on chords, because now you know how to read every single chord there is! You can open up a Real Book, or a lead sheet online, and every chord is now open to you.

To better understand these chords, it is helpful to pick one of the chords and play songs with them to really get a feel for how to use them and what these chords are for. Once you can get these chords in your fingers and in your ears, you can start effectively using them in your own compositions, and finding ways to beautify even the simplest of chord progressions with a few extensions!