The Origins of the Piano

Written by Benjamin Shparber

Torrential rain strikes the ground of a dark alleyway as a family ducks in, desperate to avoid getting any more drenched. “It’s a shortcut, trust me!” says the father, as the mother and son reluctantly follow. About halfway down the alleyway, a man materializes out of the shadows and screams “Give me all your money!” The father throws his hands up, trying to diffuse the situation, but it’s too late. The robber is spooked. Bam! Bam! Two shots are all it takes, and the mother and father lie dead on the ground. Bruce Wayne falls to his knees as his whole world collapses in just a few seconds… wait, oops. Wrong origin story.

The piano was invented in Italy around 1700, when Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731), unsatisfied with the harpsichord’s lack of ability to be played at different volumes, switched out the plucking mechanism to a striking mechanism.

What instrument was before the piano?: Meet the Harpsichord

The harpsichord’s appearance is very similar to a piano, although the number of keys is often smaller. This is because it is difficult to get a good sound from plucking very long and very short strings (corresponding to very high and very low pitches). Players who are familiar with repertoire from the Baroque and early classical era may notice that the pieces don’t take full advantage of the piano’s wide range – before the proliferation of the piano, the harpsichord was the main instrument for which these pieces were written. The keybed is in the front, and a long body of strings is behind it, which are operated by a player depressing the keys, causing a chain reaction of mechanical effects that cause a string to vibrate.

how the harpsichord makes its sound

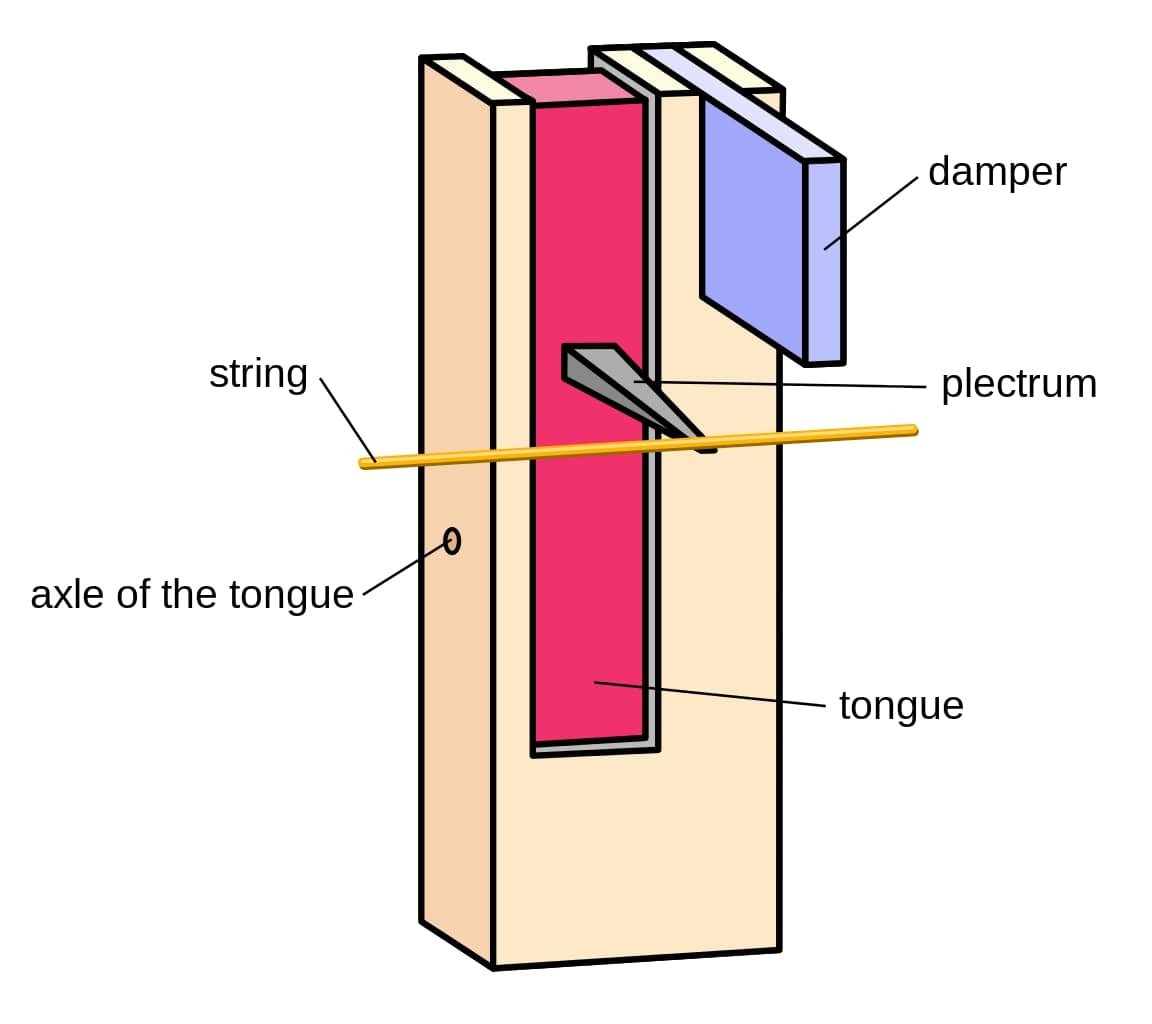

At rest, with no keys depressed, the dampers are resting on top of each string. Dampers return to rest on top of the string when keys are released as well. This is to stop the sound, otherwise you would have every string vibrating at the same time, causing cacophony. When a key is pressed, it lifts a long bar behind it that both raises the damper of the corresponding string, as well as raising the quill high and quickly enough to pluck that string, creating the sound. As each key is released, the damper returns to rest on top of the string, stopping the sound so that it does not interfere with the notes that come next.

As sustain pedals (or other pedals) were not part of the design of a harpsichord, the player had very little control over how long the sound would last other than just holding down the key.

the invention of the piano: early days

Pictured here is the very first piano, named the Cristofori piano, after its creator Bartolomeo Cristofori. It featured a striking hammer mechanism rather than a plucking quill mechanism. It took some time (until the 1880s!) before the more modern, familiar, 88-key piano was created by Steinway, still a giant in the piano manufacturing market. Pictured below is the hammer mechanism that is still in use today, largely unchanged. Just like a harpsichord, when a key is depressed, a damper is lifted off the corresponding string, and it returns when the key is released.

Technically, when a key is depressed, the only thing moving is the backcheck, which strikes the hammer mechanism, which in turn moves forward and strikes the key – this allows the hammer to return to rest instead of being pressed up against the string, muting its sound. Each of the keys of a piano has this entire mechanism behind it – you can imagine how time-consuming it must be to make one of these!

To extend the range of a piano to the full 88-keys most of us are familiar with, a few changes had to be made. To extend the range lower, the piano had to be made slightly larger to accommodate the length of the low strings. Think about how bass guitars are longer than regular guitars – the strings don’t just need to be wider, they need to be longer too. The longer the string is, the longer it takes for the vibration to get all the way down the string. This means the vibration is slower, and therefore lower. For some more information about this check out one of our previous blog posts!

To extend the range higher, a clever workaround for the thin, tiny high string sound was created: several strings were placed close together, so when the hammer hit them, it would hit several strings instead of just one, which creates a much fuller sound. If you ever wonder why it costs so much to tune your piano, this is why! A real piano has a lot of delicate moving parts, as well as over a hundred strings that all must be tuned very carefully and exactly. It’s difficult work.

Precursors to the harpsichord: string insturments

Though the harpsichord seems old to us, at the time it was a revolutionary and sophisticated piece of technology. Many different inventions had to come together to create this masterpiece. This included the keybed, which organized notes in a way both visually pleasing and easy to play. Another was the harpsichord mechanism, which both plucked the strings and dampened them after the key was released so that the note would stop. But the most important of those discoveries is strings.

The very first instruments, other than voices of course, were flutes, carved out of bone, wood or already hollow reeds. It took many, many years, and the discovery of how to preserve animal skin into leather, and some clever and skilled instrument makers, to create strings, which were first (and still can be) made from treated intestines. Nowadays, most players of string instruments use strings made of metal or nylon.

After strings were invented, many different instruments were made using their unique sound. From the lyre (popular in the Mediterranean) to the lute (of Western and Central European medieval bards) to the violin (still a common instrument today) to many, many more, different combinations of wood and stretched out strings have been created, and used by skilled players to create a myriad of beautiful music.

But to create an instrument as complex in construction as the piano or the harpsichord takes a lot more time, effort, and focused energy (as well as technology), which is most likely why it took so long (in comparison to other stringed instruments) to both invent as well as proliferate as much as it has today.

The Piano’s Massive Impact

At the time, the piano was an absolute godsend to composers everywhere. From large ensembles of 60-piece orchestras to small string quartets, the ability to play more than one note simultaneously and easily made composing a lot easier. A composer could simulate what many instruments playing at once would sound like. They could try out several different voicings of one chord before deciding on a specific one to incorporate into the piece they were writing. They could accompany singers so that they could practice, without needing all the people of the orchestra to be there at the same time. It became an essential and ubiquitous tool for composers everywhere, and in one form or another it still is.

Modern Pianos – the Advent of Electricity!

If you walk into any music store, and ask to see their pianos, most of the salespeople will look at you funny. In today’s music stores, it is rare to find a real, acoustic piano on sale. You either have to go to specialty shops, or buy them used (which is really easy, and you can often find them for free! You just have to be able to move them, which is the hard part, and why there are so many free pianos – the current owners don’t want to pay anyone to remove them!). What you will see, in may different shapes, sizes, and colors, are electric keyboards.

From tiny workstations with only twenty or so small keys, to full keyboards featuring the full complement of 88 weighted keys, to absolutely giant (and heavy) synthesizers with touchscreens, the breadth of different keyboard options can be overwhelming, even to seasoned players. (I know I can spend hours in a music store just trying out different keyboards and all the different sounds they can make).

At its core, the piano keyboard is just a set of buttons. You can apply it to a plucking mechanism such as in a harpsichord, or a hammer mechanism like in a piano, or even a giant set of pipes (like in a church organ). Small wonder that it was the choice of electronic musicians, first learning how to make synthesizers.

Due to how easy it is to make a sound on a keyboard (you just press a key and sound comes out) relative to other instruments, the keyboard has become ubiquitous as a tool for composers, songwriters, and producers as the easiest way to create a myriad of different sounds. Think how many different parts of the body have to be engaged to make a sound come out of a saxophone, let alone how much you have to practice to make that sound actually be pleasant – it’s not easy! The repetitive, logical, and visually pleasing way in which a piano keyboard is designed lends itself to a relatively quick understanding of where each note is and the relationships between them.

Many of these people are more focused on the creative process of creating a sound, which is then sampled at different pitches by the buttons on an electric keyboard, than about mastering an instrument in the same way a concert violinist would go about it. For these people, as well as home producers who just want a quick way of expressing their ideas without having to go through the possibly arduous (but extremely rewarding) process of learning an instrument, the electric keyboard is an absolute godsend.

The piano: Past, Present, and Future

The piano and its ilk are going nowhere. From its humble roots of the discovery of strings and the different sounds that they can make simply based on their tension, to the unbelievably beautiful and complex sound of a grand piano, to the myriad of sounds that can now be made by attaching a set of buttons to a computer or electric synthesizer, the piano is an integral part of every professional musician’s menagerie of instruments. It is every composer’s go-to for designing melody and working out the minutiae of accompaniment. It is present in every school as an accompaniment to their choruses and musical stage performances, present at every restaurant that plays music while you eat, and a universal symbol of the endless variety of music – the only limit is our skills and imagination.

Want to discover the worlds that learning to play the piano can unlock? Schedule a trial piano lesson at our music school near Medford and you’ll quickly see what a life-changing experience interacting with the keys can be.